Planning for Ecology Surveys

Christmas is well and truly gone, and many people are looking forward to a busy year ahead. If you are involved in submitting a planning application, or working on a new development proposal, our advice is to think ahead, and don’t get caught out by ecological surveys with a restricted season.

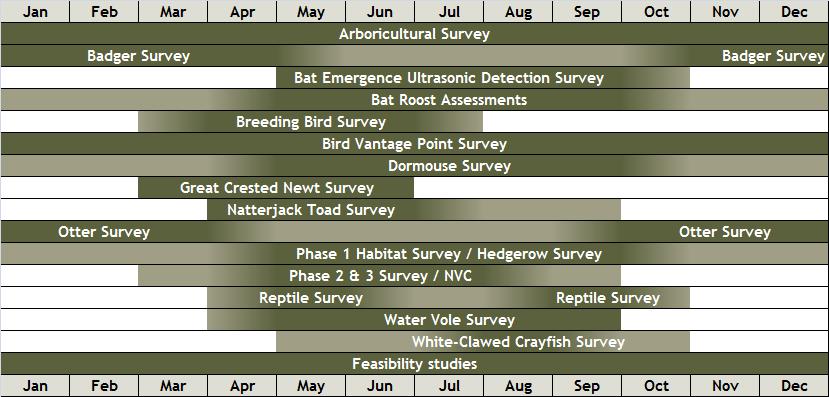

Below is our survey calendar, which will allow you to plan for commission of survey in a timely manner. WFE are usually positioned to provide a rapid response to client requests, but inevitably there are very busy periods when this is more of a challenge.

The narrowest survey season is for great crested newts, where at least 4 survey visits are normally spread between March and June. If your development has ponds nearby, these surveys may be required. As with many of the surveys, it can be problematic to remedy a missed survey window later in the season. In the event great crested newts are observed by surveys and considered to be affected by the proposal, it may take a further month or more to receive a development licence from Natural England.

Bat roost assessments for development can take place at any time of year. However, if signs of bats are found, further investigations in the form of evening emergence and/or dawn surveys will be required to support a development licence application. These surveys are seasonal, and would only be meaningful if undertaken in the time of year that bats are active, April to September.

Ecological appraisal and Phase 1 habitat survey, the look-see and scoping surveys for sites, can be undertaken at any time of year – however in areas rich in flora, a return visit may need to be made in the spring/ summer when some plant species are more visible. BREEAM and C4SH surveys are possible at any time of year although spring/ summer is preferable in terms of survey reliability.

Getting all surveys completed at the correct time of year greatly improves the prospect of a smooth and efficient passage towards planning permission, and will provide a sound basis for reaching solutions to any ecological issues. Our team are always ready to discuss particular proposals, so if in doubt, give us a call.

Rob